Like a good few million other people, I was blown away by Daisy Jones and the Six. I devoured Taylor Jenkins Reid’s beautifully crafted, clever, compelling novel, and I binged greedily on the much anticipated Prime series with its brilliant cast of characters, gorgeous costumes, lavish sets and searing, 70s-infused rock soundtrack. Daisy’s wild rock-n’roll lifestyle reminded me of my own days and nights spent on tour buses, at soundchecks, in recording studios, on photo shoots, in huge, atmospheric concert halls and auditoriums, and tiny intimate venues, and yes, at decadent parties in hotels and famous people’s houses. And while I was rarely on a stage (apart from when I watched Nirvana in the wings with L7, at London’s Astoria, and unwittingly endangered myself by hovering too near the pyrotechnics at a Metallica show in Kansas), my work as a journalist took me about as close as you could get. So, despite the difference in decades, watching Daisy really took me back in time. Even Billy Dunne looked like my music journalist boyfriend from those days, with his high cheekbones and long, messy curls.

And yet, although I gulped down the series and loved nearly everything about it to bits, just over a week after finishing the final episode, I realised there was one big, obvious flaw. The Rock Wife trope.

Billy Dunne’s long-suffering partner, Camila, is played with such effortless beauty and grace by the stunning Camila Morrone that I didn’t bat an eye while glued to my screen. But as a woman whose primary mission in life is to provide her man with loving support, unending loyalty and lyrical inspiration, her character plays directly into one of the most entrenched rock-n’roll stereotypes of all. Of course, in many ways Camila is an accurate representation from the period when many an elevated, heterosexual rock god was domestically anchored by a gorgeous tolerant and/or (wilfully) ignorant partner, but I can’t help wondering what direction the story would have taken had she been reinvented as someone with a little more fire in her belly. What if she’d had a greater sense of herself, and more self-agency? What if she’d pursued her dreams, goals and ambitions beyond motherhood and a night on the rebound with Six bassist, Eddie Roundtree? What if she’d got really fucking angry about Billy’s unresolved feelings for Daisy, and gone and got herself a life, instead of spending her time waiting for this relationally conflicted man to come home from his?

Morrone has generously spoken about the complexity of her character, and granted, Camila has her depths. But even as a valued friend of the Six, and beloved mother to her daughter, she remains primarily in a nurturing role. Her burgeoning photography practice does little to contend this, because although she is depicted as an unusually intuitive and talented artist, professional success eludes her. And she doesn’t pursue it, choosing to accept her place in the home where, with the help of her own mother, she holds the fort for Billy who periodically sweeps off the tour bus like a seasonal storm, blowing in with his artistic temperament, his fragile, swollen ego, his battles with addiction and that (not very ) secret yearning for Daisy.

Camila’s final gesture - the posthumous blessing for Daisy and Billy, many years after the implosion of the band - says it all. In terms of the story, it offers up a neat ending, but it sets a thoroughly disquieting seal on the perpetual complicity demanded and expected of the Rock Wife.

When I was a music journalist, I met a lot of rock wives and girlfriends backstage, at parties, on the road, and once or twice in their own homes. My heart would go out to them, as I imagined the hardship of missing someone for months on end, and knowing what I did about life on tour. Some were justifiably trusting long-term partners, unfussed by glamour and unimpressed with the trappings of fame, like Kurt Cobain’s ex-girlfriend, Tracy Marander, Shelli, who was married to Krist Novoselic, and the smart lawyer who had a long-term relationship with Soundgarden’s Kim Thayil. Others were unfeasibly beautiful model types in more precarious positions, having met their musicians later down the line. They tended to be more cagey, perhaps because they had learned not to trust other women with backstage passes.

I remember bonding over a love of John Fluevog shoes with the stunning girlfriend of a well-known guitarist in Chicago, only to hear him speak, much later, about his careless, callous treatment of her. Not long after this, I turned my back in disappointment when he propositioned me at a party in London, but at least he regretted his behaviour. Another musician I knew sank into despair when he couldn’t find it in him to stay faithful to the gorgeous on/off girlfriend who’d moved overseas to be with him. Thankfully, she didn’t hang about, and marched off into a media career leaving him to dwell on his self-inflicted wounds and his out-of-control amphetamine habit.

Maybe things are different now, but back in the 1990s, it was understood and accepted that rock stars were sexual monsters and the entire industry fed and upheld their appetites. Very few of them appeared to be capable of sustaining a relationship, despite what some of them claimed. A journalist friend who had long-standing professional relationships with some of the biggest rock stars in the world, once told me how the high-school sweetheart of a massively successful singer was completely unaware of her husband’s continual cheating. Apparently, the entire road crew complied with this lie, and went to great lengths to clear away the evidence whenever she popped up on tour. This particular artist still presents himself as a devoted family man with wholesome American values. Over the years it’s become integral to his brand, but my friend will always remember him happily surrounded by groupies.

I think what really bothers me about the Rock Wife trope is that it reinforces the ancient notion of woman as container, both physically and psychically. As an archetypal image the containing woman is literally a receptacle, or a vessel, waiting to be filled, serving to harness and hold the emotions, ideas and bodies of others. And I make no apologies for my wholesale rejection of this undermining perspective. (It was one of the main issues I had with traditional Jungian theory when I studied my MA.)

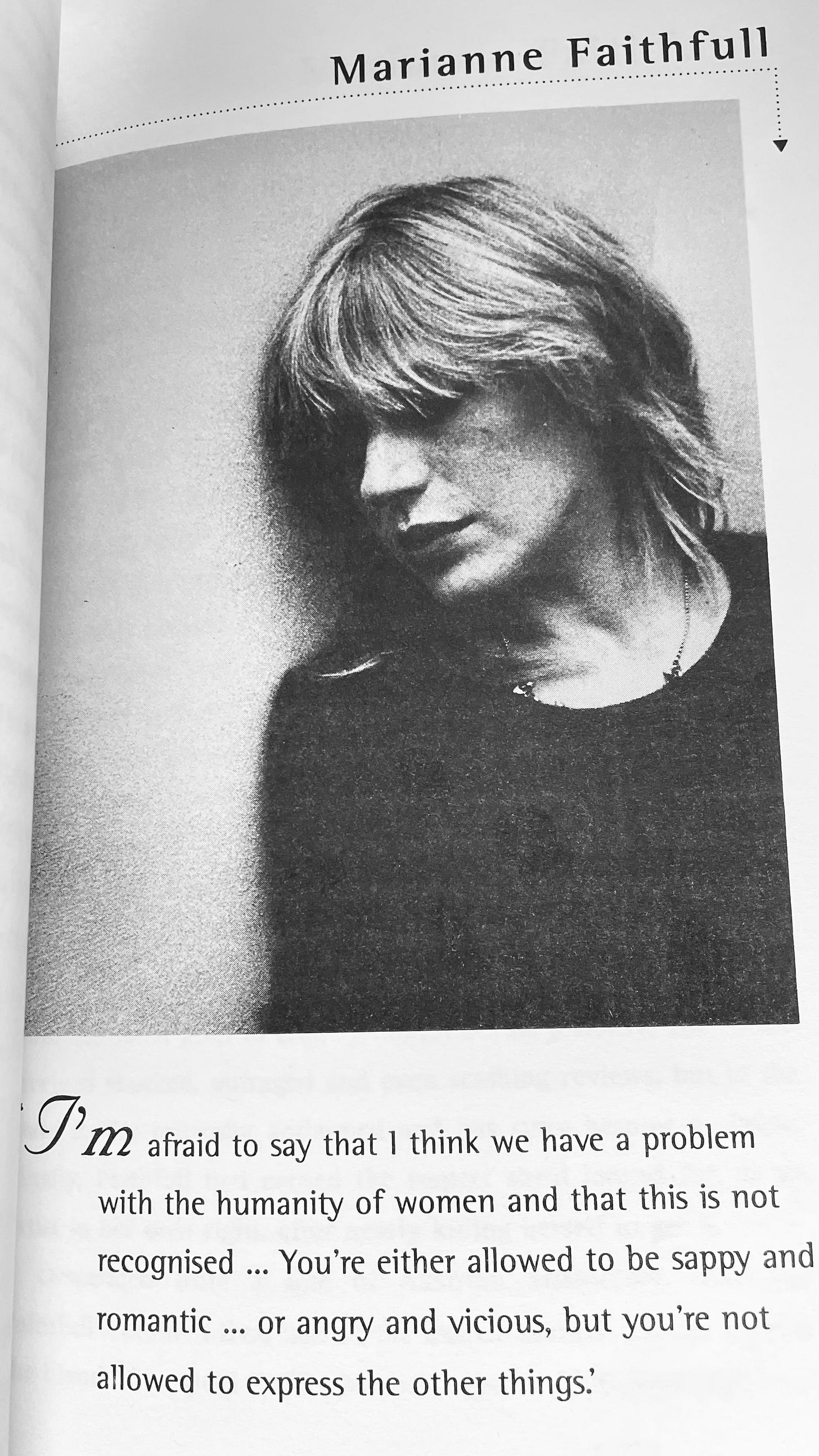

When I interviewed Marianne Faithfull in 1993, for my first book, Women, Sex and Rock’n’Roll: In Their Own Words, she told me how she gave up her singing career “to try and live the life of a courtesan with Mick (Jagger)”. And this is how she explained her role in his creative process at the time of the Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet album, in 1968:

“To meet a woman like me for Mick Jagger, and for Keith Richards to have Anita (Pallenberg) was wonderful. They had access to our minds, much more than our bodies, which is what was so interesting, because we shared our dreams with them. And I didn’t mind sharing my dreams. I didn’t feel resentful at all.

“I didn’t mind because it was so fascinating. I didn’t think of it as being a muse and I still don’t. It was more interesting than that. I think Anita and I were the only women at the time for those two people to write those songs in that way, and that’s how it was. A muse has a much more powerless role, and I didn’t have a powerless role, I had a very, very strong role. Everything Mick wrote I heard first and I did a lot of shaping and changing and fixing. And everything Keith wrote I heard too actually, because we were all so close.”

And yet, for all her perceived creative power, she also told me how she soon became “bored and restless” because she wasn’t “really doing anything”.

“I couldn’t bear the person I was with Mick and I did want to destroy it. I don’t blame Mick, I really don’t… but what are you supposed to do? Damp yourself down? I know that women damp themselves down , but it’s easier for women to do that because there’s a sort of pattern for you. I mean, I did it, and it nearly killed me…. I felt as if I were in a goldfish bowl and there was a lot of hatred and envy and jealousy from other women, and it was really, really bad and it was a thing I didn’t know how to deal with.”

Her way of dealing with these feelings, at the age of 22, was to “go on the street and shoot dope.”

“I ended up thinking the best thing I could do was be a junkie and live on the street because that’s where I belonged. And actually it was a very good idea, because I did get my anonymity back.”

Years later, in 1979, Faithfull established herself as a serious musical force with her album, Broken English. But her extreme, self-destructive response to the experience of finding herself in the role of Rock Consort remains extremely telling.

It’s not as simple as Camila being portrayed as a pushover, because she isn’t. Like Morrone says, her character is more nuanced than that. And let me be clear that I believe there is enormous value in building a safe and loving home for children and partners, and I know that many women actively, freely choose to do this with their lives. But that’s not my issue with Camila’s particular role in this particular story. My focus here is firmly on her function as the reliable hearthstone to Billy’s creative force and single-minded ambition, because I can’t ignore the questions this raises.

As Marianne’s experience highlights it’s not enough to be a muse, even if you do earn yourself a song-writing credit. Daisy Jones certainly doesn’t think so either, and that’s what gives her character the edge. As she says:

"I had absolutely no interest in being somebody else's muse. I am not a muse. I am the somebody.”

And that’s why I identified with Daisy, not Camila.