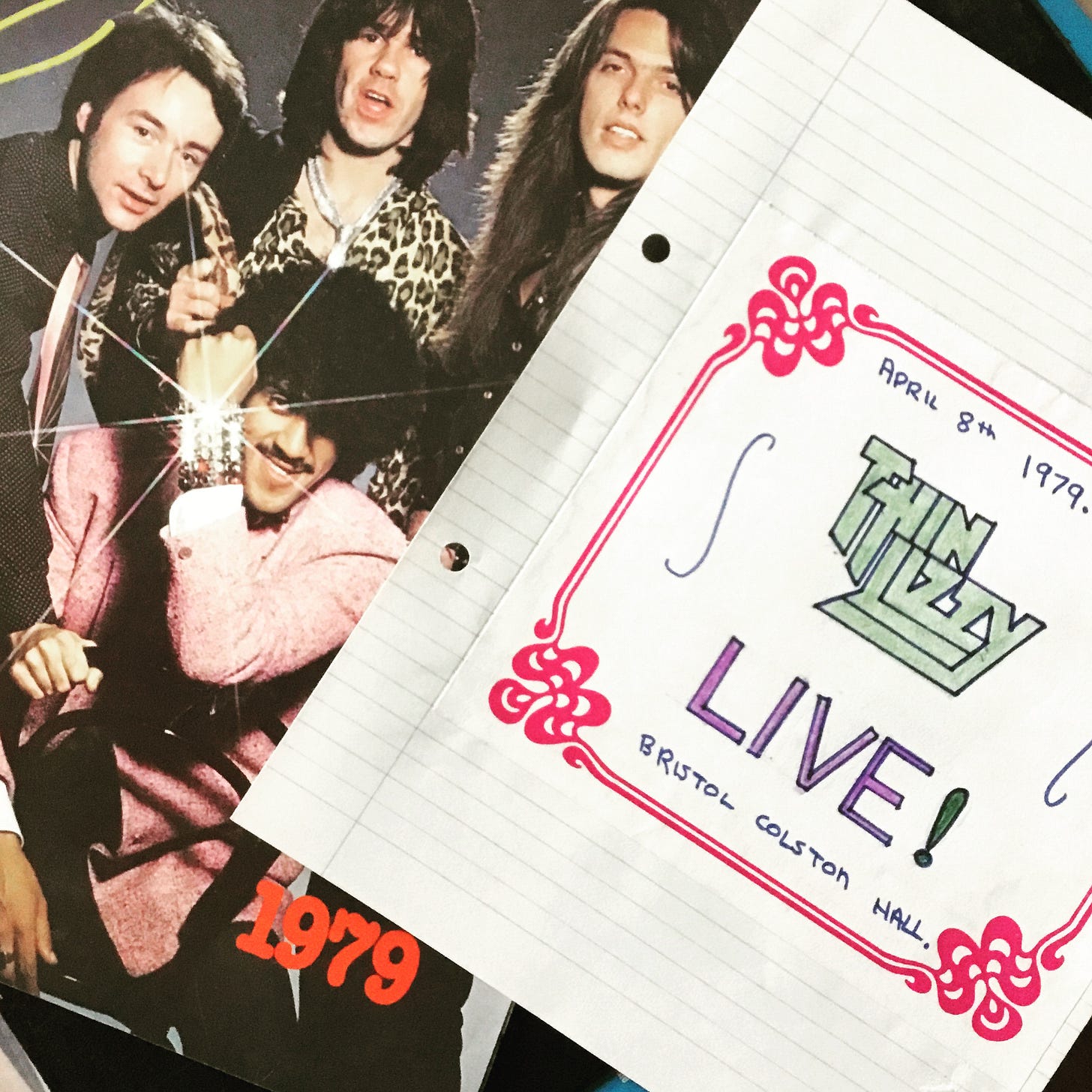

When people ask me how I became a music journalist, I usually tell them it was a matter of naivete, ignorance and bloody-mindedness, but recently I realised there might have been more to it. Not so long ago, I was looking through some old folders for memoir research, and came across my very first ever live review - of Thin Lizzy at Bristol Colston Hall (a place which has thankfully now been re-named), written in 1979, when I was just 13…

I was so excited about this gig. For weeks after buying my ticket, I prayed to a god I didn’t believe in to make sure that nothing happened to stop me going. By the time we finally arrived at the venue, intact, uninterrupted, on time, safe and sound, tickets in hand, I was shaking. When the band erupted on stage, in an explosion of lights and guitars, I turned to my friend, Simon, and screamed. We both did.

I couldn’t believe my eyes. I couldn’t believe this was really, truly, actually Thin Lizzy - or, more specifically, Phil Lynott, in the flesh, in living breathing extremely-in-front-of-me real life. It was like being in a dream, and no doubt my teenage euphoria was compounded by the fact that this was my first proper live concert, apart from the Eric Bell Band. I’d seen Eric at my local Technical College, but the only reason I went was because he’d played with Thin Lizzy during the 1970s. The Bristol gig was next level, and at 13, I felt like I was going to burst.

My review was quite listy. Not much more than song titles, descriptions of the band’s outfits, and little things they did and said on stage. And I clearly didn’t care about the syntax. I simply wanted to capture the memory. Many years later, an old schoolfriend told me that when I was 14, I announced I was going to become a music journalist and while I don’t remember saying that, nine years later, that’s exactly what I did. Evidently that first delirious gig experience had planted something of a seed.

I moved to London in 1984, to study English at the Polytechnic of North London. After under-achieving quite spectacularly at school, thanks to being diverted from academia by Music, Music, Music, Boys, Boys, Boys, and Clothes, Clothes, Clothes, this was the only institution in the country willing to take me on. PNL’s arts campus, located in what was then the slightly scruffy neighbourhood of Kentish Town, was a creative and socio-political hub. While there I befriended a former employee of Vivienne Westwood’s, a model who’d dated Adam Ant as well as ABC vocalist Martin Fry, and an entire post-punk squatters’ community, who occupied buildings throughout Islington and Hackney. The bar and canteen were humming with people who’d go on to form bands including Moose, Lush and the Pale Saints. And PNL is where I first met Ben Harding, who ended up joining the Senseless Things on guitar.

When I first saw Ben’s band, I was working as a temp for a travel company, with the intention of saving money for a trip to Thailand. It was 1988, and I’d spent a few months since leaving PNL bouncing between the now-defunct Inner London Education Authority’s amazing adult classes, learning tap and jazz dance, art and textiles, and volunteering at the Islington Arts Factory. I’d also taught myself to type at one of ILEA’s drop-in centres, in preparation for temping. Now, at the travel company, I was constantly making mistakes, and bored out of my mind, but I was working in the same building as Spotlight Publications, who published music papers Sounds and Kerrang! I could see the Kerrang! journalists from one of the office corridors, and they looked like they were having a lot more fun than me. So, I decided to write a review of Ben’s band, made a couple of copies, and dropped them off at Spotlight’s reception desk on my way to work one morning.

Each week, I checked the papers in the newsagents to see if I’d been published, and after about three weeks, fed up with wondering what was going on, I called Robbi Millar at Sounds from the phone box outside my flat on Camden Road to ask her when she was going to print my review. Needless to say, she was somewhat taken aback and promptly told me she had a backlog of four months’ worth of reviews to get through, and effectively - who the hell did I think I was? I couldn’t believe my ears. How dare she speak to me like that, I thought, utterly outraged. Who the hell did she think she was, more to the point? I marched away from that phone box on fire, absolutely determined to get my bloody review published, one way or another.

For the next couple of weeks or so, I told everyone I knew that I was going to become a music journalist and before long, I got a tip-off. One summer night, at a Hoodoo Gurus gig at the Electric Ballroom in Camden, my friend Mike said that one of his housemates, a publicist for London’s iconic comic bookstore, Forbidden Planet, knew of a rock magazine that needed more freelancers. The only drawback was that this was Metal Hammer, which was widely regarded as the joke equivalent of Kerrang! Still, what the hell, I reasoned, and set off to my trusty phone box, where I managed to fix up a time to meet Chris Welch, the magazine’s editor.

I was incredibly nervous on my way to the Metal Hammer offices. It was a hot day, and I remember catching a couple of buses to Paddington, and walking through the streets towards an extremely well-manicured square full of white, Regency houses opposite a slice of immaculate garden behind black railings. It didn’t feel right. It was so posh. Surely a rock magazine couldn’t possibly be housed here?

But yes, at number whatever-it-was, behind the expensive facade, up a flight of stairs, there it was, Metal Hammer HQ. I was greeted with a slight sneer by Claire at reception, and shown through a noisy office of journalists (so much hair in the late 1980s) and into the quiet oasis of Chris’s private room, where photos of Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page and Marc Bolan lined the walls. I didn’t know it at the time, but Chris had been a Melody Maker journalist in the 1970s, and was still good friends with a handful of rock legends, some of whose kids were at the same private school as his own. He was dressed very smartly, more like a casual businessman, spoke softly, and had a kind, gentle manner. After a very brief chat, he introduced me to Jane, the reviews editor, who shoved a handful of albums into my arms and told me I’d be on the guest list for a gig (Death Angel, I think…) the following week at The Dome in Tufnell Park.

I walked out of that office on air. I had no idea about any of the bands I’d been commissioned to review, and no idea how to enter a venue via the guest list. I had no idea about anything at all, except that I loved music, and now I was about to become a published writer. Writing was the only thing I’d ever been any good at, but I’d never considered how I might turn it into a job. Not before now. I didn’t even think to ask Chris about money or rates of pay, which was a good thing really, as music journalism has never been a way for anyone to get rich. But it gave me the absolute best possible life I could have had in my 20s, and I will always be grateful to Chris for taking a gamble on me, as a naive, unpublished writer, and to Robbi Millar, for making me so fucking angry, defiant and determined, and to Mike, of course, for the tip.

Sometimes it’s better not to know the protocol. I’m glad I didn’t know I was meant to spend years in poky little, (preferably regional) bars, churning out overly wordy, fact-filled reviews of up-and-coming bands, pestering editors with letters and samples of my work before finally getting my name in print. And I’m glad I didn’t stop to think about the distinct advantage afforded to male journalists at a time when women were mostly still writing about pop, rather than rock music. I got published through a blend of ignorance, indignance, optimism, just enough self-belief, and, yes, luck, because being in London, with access to an amazing circle of creative friends was also key. But it was a matter of right time, right place rather than nepotism, and I’m glad I can say that, knowing what I do now about the publishing industry and the world of journalism.

There’s a lot more to explore in all of this, which I’ll be doing in future posts. Because while I was trusted and respected by some, I was also deeply resented, and in one case bullied, by bitter male colleagues for finding myself a fast track into writing. And now that I’m teaching aspiring young writers at university, I’m aware of the need for realistic expectations as well as hope and luck. During a recent interview with a local radio station, I explained why writers need resilience and perseverance, because getting published is difficult, and continuing to be published is arguably harder. And I didn’t have much of either at the beginning of my career, so I had to develop both pretty fast. And yet, my own experience also taught me to quite literally reach for the stars (well, ok, not literally). The point being that I wasn’t a trained journalist, or the daughter of a famous rock musician, or the cousin of an established photographer. I was simply a girl who believed she had as much right to an extraordinary life as the next person, I knew I could string a sentence together, and I had the courage to knock on a few doors. So while I want my students to have a realistic idea of what they’re up against, I also want them to feel confident and worthy of taking a shot, because you never know until you try.

Do you?