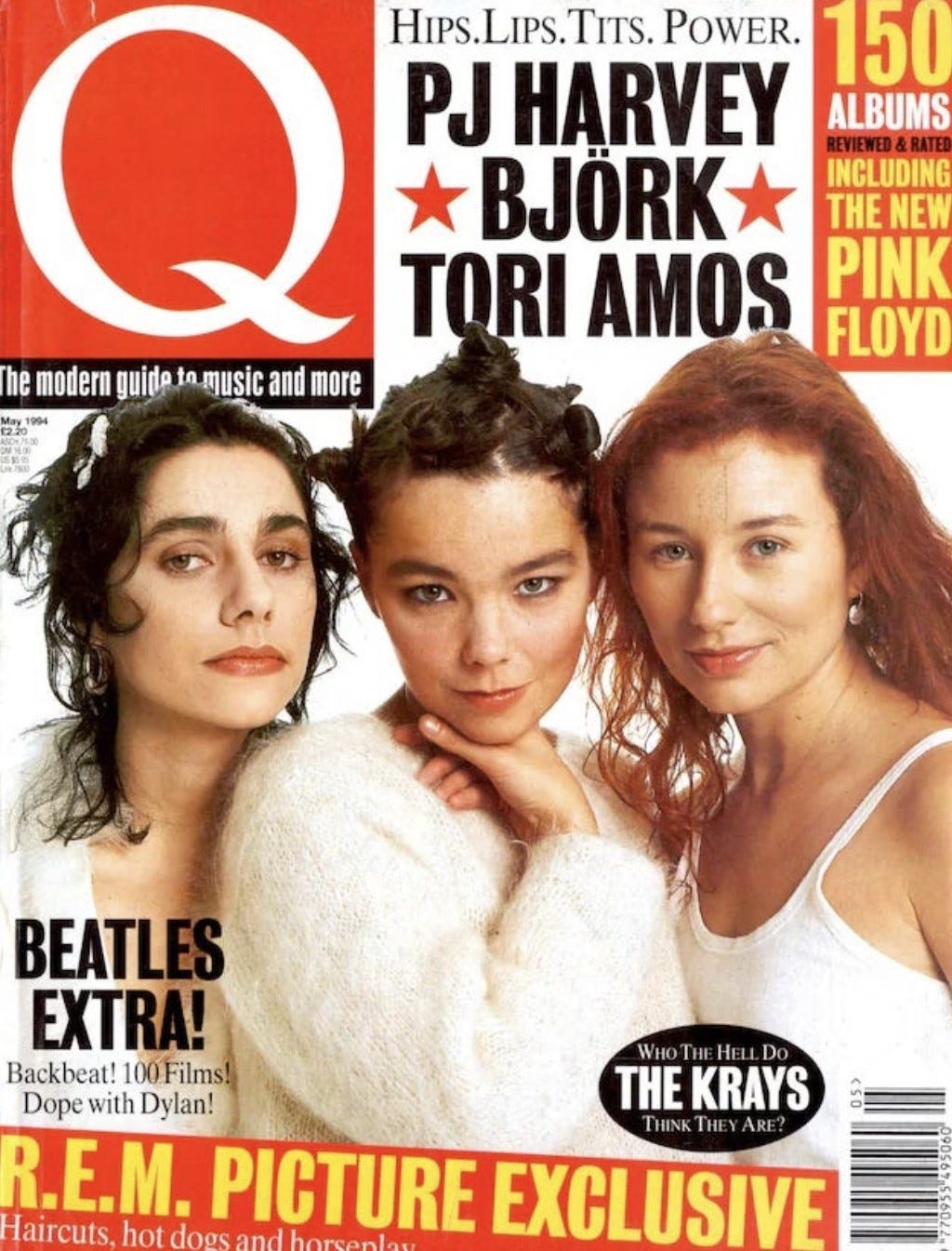

1994: That controversial Q cover, and my first book

(Is it really 30 years ago??!)

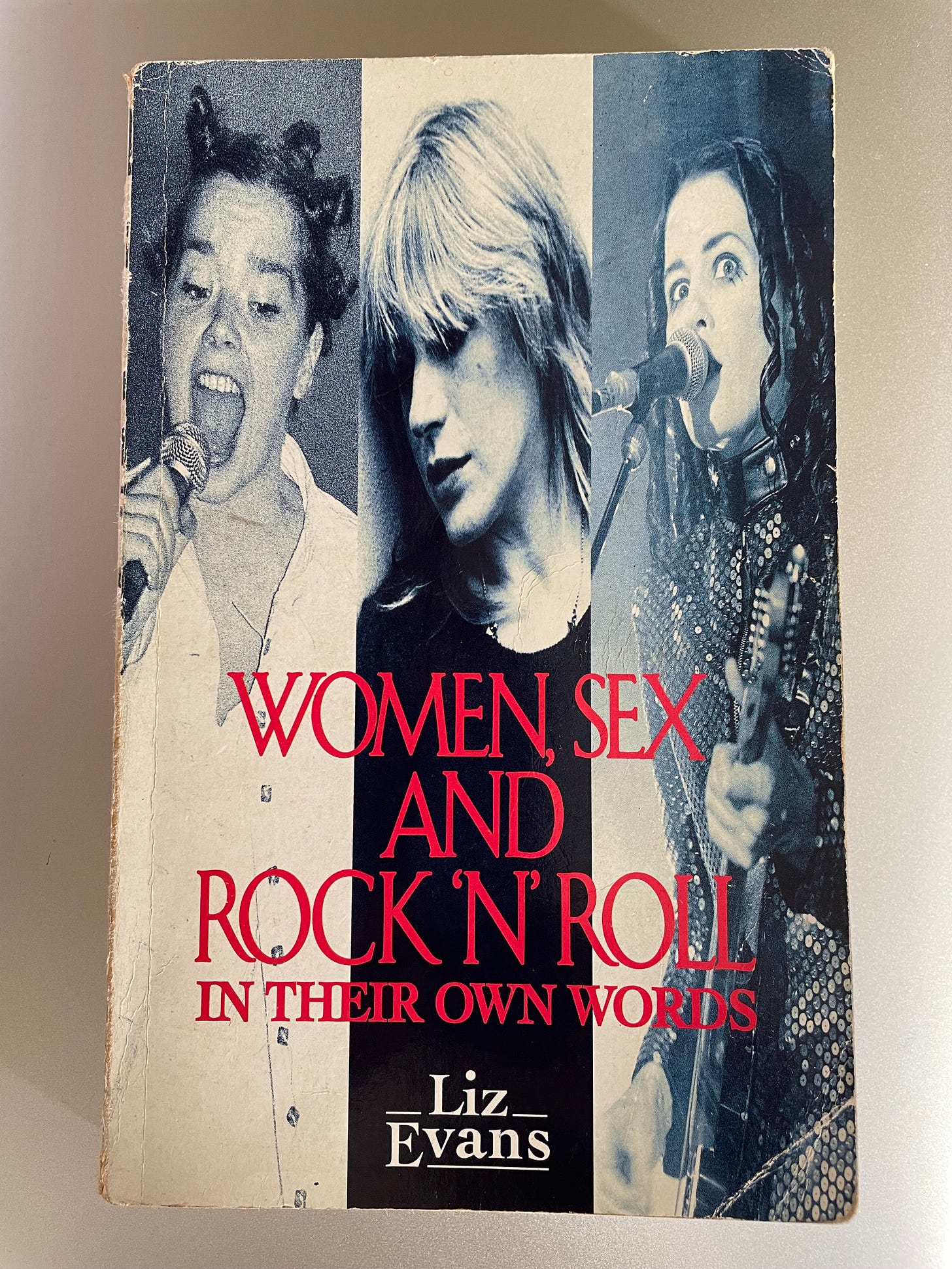

It’s hard to believe that this infamous Q magazine cover is more than 30 years old (thank you Sam Baker for the prompt!), not least because it means my first book, Women, Sex and Rock’n’Roll: In Their Own Words (Pandora Press) appeared three decades ago now. With things gearing up for the August publication of Catherine Wheel (Ultimo Press), my debut novel, I had completely forgotten that my first non-fiction book on women and rock culture – virtually the first of its kind, that would go on to lead a spate of others – was published in 1994.

Seeing this cover again reminded me of how regressive the predominant attitude towards female musicians was back in the 1990s. But it wasn’t just music fans, or even the structural sexism of the music industry that was the problem – it was also the music papers. I clearly remember how fed up and irritated women like Tori and Bjork were with ignorant male journalists asking them dumb, patronising, offensive questions because they both told me, when I interviewed them for my first book, while others, like L7 (with whom I was pretty friendly at the time), refused to partake in the project because they were so concerned about being lumped into some generic ‘Women in Rock’ category. I was disappointed not to have their involvement, but as someone who witnessed and directly experienced the bias of the 1990s music press, I got it. In fact, resentment at being lumped together on the basis of gender was arguably the only thing that united Tori, Polly and Bjork back in 1994, as they all expressed at the time to Q’s journalist, Adrian Deevoy.

Unlike now, the 1990s was awash with music magazines, and I wrote for nearly all of them in the UK at one time or another, plus a few in the US and Australia. But not Q. Never Q. I was never blokey enough. Co-founded in 1986 by Mark Ellen and David Hepworth, a couple of middle class, middle of the road, middle aged white guys known for presenting the ultimate Old Man’s music programme, The Old Grey Whistle Test, Q was a relatively pedestrian publication with a predominantly male staff. Given that Ellen was an ex-Oxford graduate, who once played bass in a band with Tony Blair just so he could meet girls, this was hardly surprising. Drawing its editorial team from the small, elite pool of male music journalists, who all seemed to circulate between the NME, Select, Mojo and The Word, Q gave short shrift to women writers, and this never seemed to change. I have a friend in London who is a highly acclaimed music journalist, author, biographer and academic, and even she was consigned to writing tiny reviews, like a teenage intern, for the magazine.

In the 1990s I worked extremely hard, but despite publishing two books on women and music, covering Riot Grrl and rock music for the NME, becoming a staff writer at RAW and one of Kerrang!’s foremost feature writers, and contributing music articles to i-D, Elle and The Guardian, I was often beseiged by the structural sexism of the times. This was largely down to the patriarchal authority of publications like Q, the refusal to recognise or address sexual harassment, workplace and gender-based bullying, the constant merry-go-round of the male editorial battalion, and the small number of women who complied with their systems, because sadly (and to a point, understandably) there were a few female music journalists who simply weren’t interested in building supportive professional networks with other women. We all knew there were only so many seats at the table. This was once spelled out to me by an NME journalist, who explained the ‘special position’ afforded to a female writer who was permitted to write features - a privilege I also had at the NME, but in my case, it came with a barrel load of resentment from nearly all the male staff.

Having a boyfriend who was also a music journalist made things even more difficult. Socially, we had a ball. Between us, we were invited to all the best music industry gigs and parties in London for a solid five years, and we had a great life together during those years. And not that it was a competition, but as a writer, I achieved more in terms of publishing contracts and my diverse portfolio. Nevertheless, he enjoyed greater respect within the music industry. At the time, this was infuriating and upsetting, although it wasn’t something I reflected on after leaving the field. But when I presented a short talk in relation to Life Writing at an academic symposium a year ago, a professor in attendance spoke of the unfair challenges she had faced in her career, as the young female partner of a male academic. Oh, I remember thinking, as she responded to my talk, so that really was A Thing!

Eventually, after starting work on a third book about sexual politics and rock culture for a reputable publisher, I decided I’d had enough. I was exhausted and jaded and fed up with constantly trying to prove myself as a writer. I pulled the pin on the book, partly because my publisher paired me with an editor who was writing about porn, and partly because they shared my detailed synopsis with another of their authors, who then produced a very similar book to the one I was planning. At least they let me keep the advance.

Ten years of sustained misogyny in the workplace was a lot to contend with. I loved my extraordinary, brilliant job, but the treatment I endured complicated my career in ways that became unsustainable, and my confidence wasn’t properly restored until I embarked on an MA in 2001 and began publishing academic articles.

Now, 30 years or so later, I’m working on a novel about two women in a band and planning a memoir. Currently, there’s a lot of conversation about the need for women’s voices, and the importance of reviving and preserving our work, as women, particularly as we age, so hopefully I can make a useful contribution by writing myself back into the system, in more than one genre too.

It’s hard to know how much has really changed, but so important not to stay silent.

I love this Liz - the spiral is spot on! We keep coming back to themes (obsessions, interests) built up over a lifetime but each time we have moved on a little, our perspective is different, we aren’t circling round but taking what we have learned forward.